Before gaining international renown for Scarborough College, Gund Hall at Harvard University and the iconic CN Tower, John Andrews was a young architect at Toronto’s John B. Parkin Associates. During his tenure at Parkin he designed the Simpson’s department store at Yorkdale Shopping Centre, opened in early 1964 as the largest indoor shopping mall in the world and a landmark in the development of suburban Toronto.

In contrast to the raw concrete and sculptural forms of Andrews’ later Brutalist work, the Simpson’s store shows the influence of New Formalism, a fanciful, decorative neoclassical style popularized in the late 1950s and early 1960s by American architects Edward Durell Stone and Minoru Yamasaki. Accordingly, pairs of arched columns line the perimeter of the building, curving upward into deep parapets that gently flare outward at the top. The precast concrete cladding, when new, was a pristine white and glittered with Georgian quartz aggregate; inset wall panels at the ground level were Simpson’s blue. The building’s careful detailing extended to the undersides of the entrance canopies, which were decorated with candy stripes of glass tiles in brilliant orange shades. Originally opening onto the mall was Simpson’s Court, a high-ceilinged, airy public space with marble and terrazzo floors, a reflecting pool, splashing fountains, tropical plants and a winding helicoidal staircase leading to a restaurant overlooking the court below. Spotlights set into a ceiling of undulating Moorish arches provided a final exotic touch.

In 1978 the Hudson’s Bay Company acquired Simpson’s, and in 1991 Simpson’s Yorkdale was remodeled as a Bay store after the Simpson’s brand was discontinued. The building’s exterior remains much the same, although the white concrete panels have become badly discoloured. Simpson’s Court has been largely subsumed by rows of cosmetics boutiques.

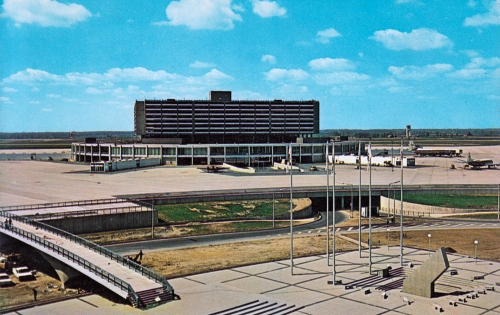

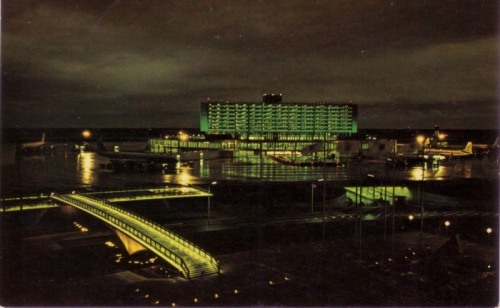

Born in Australia, John Andrews received an architectural degree from the University of Sydney before entering the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University. A submission by him and three Harvard classmates was selected as a finalist in the Toronto City Hall competition, which led to his recruitment by John B. Parkin Associates in 1958. Among the buildings he was responsible for during his three years with Parkin were the Primrose Club (273 St. Clair Avenue West, 1960; demolished), the Federal Equipment plant and offices (88 Ronson Drive, 1960), Bawating Collegiate and Vocational School (750 North Street, Sault Ste. Marie, 1961; demolished) and the control tower at the new Toronto International Airport (1964; demolished). In 1962 Andrews established his own firm and became chairman of the University of Toronto’s school of architecture, a position he held until 1967. His North American work during the 1960s and 1970s includes Scarborough College, the South Residence at the University of Guelph, the Weldon Library at the University of Western Ontario, the proposed Metro Centre redevelopment of the Toronto railway lands, the Miami Seaport Passenger Terminal, Gund Hall for the Graduate School of Design at Harvard University and, probably most famously, Toronto’s CN Tower.

In 1972 Andrews returned to Australia, where his best-known buildings include the King George Tower in Sydney, the Cameron Offices for the Australian federal government in Belconnen, Canberra and convention centres in Sydney, Melbourne, Perth and Adelaide. He retired from full-time practice in the early 1990s with many honours, among them a Massey Medal and an OAA 25-year award for Scarborough College, a Gold Medal from the Royal Australian Institute of Architects and an Honor Award from the American Institute of Architects.