Buoyed by the success of their groundbreaking Don Mills garden city, in 1957 Don Mills Developments Limited launched its Parkway West community. Located southwest of York Mills Road and the Don Valley Parkway, just a tee shot across the Don River from the original development, Parkway West was a more traditional suburban residential enclave targeted at the middle to upper-middle professional and managerial classes.

The planning of Parkway West largely followed the principles established for Don Mills. The wide boulevards of Laurentide Drive and Three Valleys Drive gently wound down the sloping hillside, linking a network of curving crescents and cul-de-sacs that extended south and west to the edges of the Don River ravine. Lots were substantial, boasting wide frontages, generous setbacks and unbroken vistas of well-kept lawns. Amenities included the luxurious Donalda Club, whose golf greens blended with the naturalized parks and greenbelts of mature trees.

The development model also followed that of Don Mills: Don Mills Developments built the civil infrastructure and sold serviced lots, either to approved design-builders or to private owners who then directly commissioned their own residences. The Yarmon residence at 12 Spinney Court, designed by Henry Fliess, is a notable owner-commissioned example.

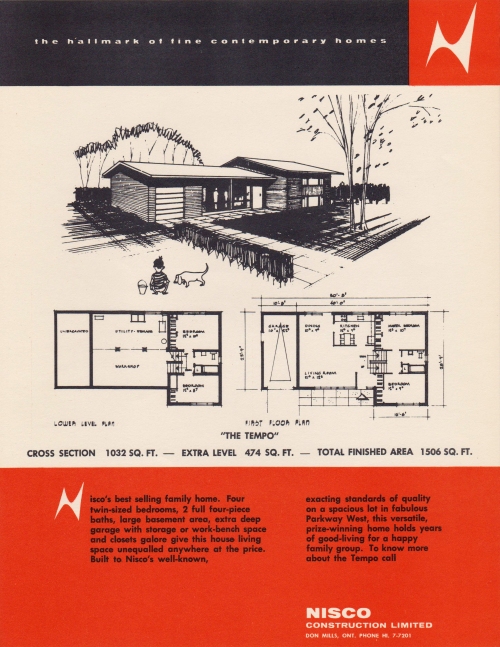

Nisco Construction was one of the Don Mills builders also selected for Parkway West. In the spring of 1957 the firm brought to market 14 houses in five different styles, with prices ranging from a Crest semi-detached at $17,500 to an Executive on a prime ravine lot at $27,900.

The architecture of the Nisco offerings was a conservative, moderate Modernism, less advanced than some of the original Don Mills housing but in line with the rest of Parkway West and similar upscale Toronto-area developments. All but the Crest incorporated then-new split-level planning, combining the space efficiency of a two-level home with the convenience and low-slung roofline of a single-storey rancher. The fashionably low profiles were further enhanced by embedding the lower storeys partly below grade or into the slope of the lot.

Interior planning emphasized the primacy of family life, with the open-plan living / dining area and kitchen as the communal nucleus of the home. There were no private ensuite bathrooms, even in the top-of-the-line Executive, although Dad was given a den to escape to with his fly-fishing gear and Canadian Club. Attached carports or garages were a prominent feature of all models, a place to display the bejeweled tailfins of the latest Buick Roadmaster or Monarch Turnpike Cruiser.

Despite the emphasis placed upon the architects of the original Don Mills development, the authorship of the Nisco homes in Parkway West is unclear. Toronto architect Norman R. Stone is credited with the design of the Executive; the others are unattributed and may also be by Stone, although the Bancroft closely resembles earlier Don Mills houses by James Murray.